Notes from a Small Population: 40+ places with under 500,000 inhabitants

DiscussãoReading Globally

Entre no LibraryThing para poder publicar.

1spiralsheep

(Please note that this theme runs from January to March 2021 but I've posted early to allow readers to access a recs list in advance due to many members experiencing reduced library and bookshop services or, if they're lucky, increased likelihood of midwinter gift books. The Russians Write Revolutions quarterly theme continues until the end of December 2020.)

This quarter visits the many places with a population of under 500,000 permanent inhabitants.

The theme of a population under 500,000 gives an interesting group of 40+ disparate places with the largest common geographical group being island nations. The official and unofficial languages are equally varied, with dozens of local languages, including Italian, in addition to the colonial influences of English, French, Dutch, Portuguese, Spanish, and Arabic.

Although you could extend the group to under 1 million population which adds the Maldives, Cape Verde, Suriname, arguably Western Sahara (Sahrawi / Morocco), Luxembourg, Montenegro, arguably Macau (China), Solomon Islands, Bhutan, Guyana, Comoros, Reunion (France), Fiji, and Djibouti.

I found it difficult to decide whether to list the following suggestions by population, geographically, or alphabetically, so my apologies if I haven't used your preferred categories. I also apologise for leaving out diacritical marks but touchstones doesn't seem to appreciate them.

I've included various forms of colonial overseas territories so you can decide for yourselves whether they count or not for this theme, with the UK and US territories separated as per Reading Globally norms: some overseas territories are self-governing and politically distinct from the colonial power; some have disputed governance; some are culturally or linguistically distinct from the colonial power; some are mostly military bases with few permanent local inhabitants.

I've also included notable non-fiction which had global impact, such as Alfred Dreyfus' prison memoir, Aime Cesaire, and Frantz Fanon, because I know the group tolerates non-fiction when it's interesting enough and on topic (and, let's be honest, much autobiography is a form of fiction anyway). I've listed a few selected books catering to previously stated interests, e.g. prison writing, gay fiction, crime novels, anthologies, and children's books, but many more are available.

Please feel free to add further book suggestions and any corrections in comments!

This quarter visits the many places with a population of under 500,000 permanent inhabitants.

The theme of a population under 500,000 gives an interesting group of 40+ disparate places with the largest common geographical group being island nations. The official and unofficial languages are equally varied, with dozens of local languages, including Italian, in addition to the colonial influences of English, French, Dutch, Portuguese, Spanish, and Arabic.

Although you could extend the group to under 1 million population which adds the Maldives, Cape Verde, Suriname, arguably Western Sahara (Sahrawi / Morocco), Luxembourg, Montenegro, arguably Macau (China), Solomon Islands, Bhutan, Guyana, Comoros, Reunion (France), Fiji, and Djibouti.

I found it difficult to decide whether to list the following suggestions by population, geographically, or alphabetically, so my apologies if I haven't used your preferred categories. I also apologise for leaving out diacritical marks but touchstones doesn't seem to appreciate them.

I've included various forms of colonial overseas territories so you can decide for yourselves whether they count or not for this theme, with the UK and US territories separated as per Reading Globally norms: some overseas territories are self-governing and politically distinct from the colonial power; some have disputed governance; some are culturally or linguistically distinct from the colonial power; some are mostly military bases with few permanent local inhabitants.

I've also included notable non-fiction which had global impact, such as Alfred Dreyfus' prison memoir, Aime Cesaire, and Frantz Fanon, because I know the group tolerates non-fiction when it's interesting enough and on topic (and, let's be honest, much autobiography is a form of fiction anyway). I've listed a few selected books catering to previously stated interests, e.g. prison writing, gay fiction, crime novels, anthologies, and children's books, but many more are available.

Please feel free to add further book suggestions and any corrections in comments!

2spiralsheep

Americas

Saint Pierre and Miquelon (France)

• Francoise Enguehard, no reviews but fiction in French and English

French Guiana (France)

• Leon-Gontran Damas aka Lionel Cabassou, poetry, essays, and short stories, in French and English translation

• Auxence Contout, poetry, essays, and short stories, in French

• Sylviane Vayaboury, novels in French

• Rene Jadfard, novels in French

• Five Years of My Life is famous prison writing by Alfred Dreyfus

• Papillon is prison escape writing by Henri Charriere

Belize

• Zee Edgell, novels Beka Lamb, Time and the River, In Times Like These, and The Festival Of San Joaquin

• Zoila Ellis, short stories in On Heroes, Lizards and Passion

• Anthologies Memories Dreams And Nightmares: A Short Story Anthology By Belizean Women Writers and Snapshots Of Belize, An Anthology Of Short Fiction

Saint Pierre and Miquelon (France)

• Francoise Enguehard, no reviews but fiction in French and English

French Guiana (France)

• Leon-Gontran Damas aka Lionel Cabassou, poetry, essays, and short stories, in French and English translation

• Auxence Contout, poetry, essays, and short stories, in French

• Sylviane Vayaboury, novels in French

• Rene Jadfard, novels in French

• Five Years of My Life is famous prison writing by Alfred Dreyfus

• Papillon is prison escape writing by Henri Charriere

Belize

• Zee Edgell, novels Beka Lamb, Time and the River, In Times Like These, and The Festival Of San Joaquin

• Zoila Ellis, short stories in On Heroes, Lizards and Passion

• Anthologies Memories Dreams And Nightmares: A Short Story Anthology By Belizean Women Writers and Snapshots Of Belize, An Anthology Of Short Fiction

3spiralsheep

Caribbean 1

Caribbean Netherlands (Netherlands)

Sint Maarten (Netherlands)

• Lasana M. Sekou is a prolific author, e.g. Brotherhood of the Spurs, and edited Where I See The Sun: Contemporary Poetry in St. Martin

Saint Kitts and Nevis

• Caryl Phillips, novels A State of Independence, The Final Passage, and Cambridge

• Bertram Roach's novel Only God Can Make a Tree

Dominica

• Jean Rhys is famous for the novel Wide Sargasso Sea, but she also wrote a few short stories reflecting her childhood background which are in Sleep It Off Lady

• Phyllis Shand Allfrey, novel The Orchid House, short stories in It Falls into Place, and poetry

• Marie-Elena John, novel Unburnable

Antigua and Barbuda

• Jamaica Kincaid, novels including Annie John, The Autobiography of My Mother, Mr Potter and Lucy, short stories in At the Bottom of the River, and travel essays including A Small Place about Antigua and Talk Stories about the US

Aruba (Netherlands)

• Three of Nydia Ecury's short stories are in The Whistling Bird: Women Writers of the Caribbean edited by Pierrette Frickey

• Henry Habibe is a poet who occasionally writes in Spanish or Dutch

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

• Cecil Browne's short stories in The Moon Is Following Me and Feather Your Tingaling (or Cassie P Caribbean PI if you must)

• H. Nigel Thomas, novels (some set in Canada), Spirits in the Dark has a gay protagonist

• Shake Keane was a legendary jazz trumpeter (and poet)

Grenada

• Merle Collins, Lady in a Boat poetry, Angel and The Colour of Forgetting novels, and The Ladies are Upstairs short stories

• Jean Buffong, novels such as Under the Silk Cotton Tree

• Jacob Ross, mostly crime novels Black Rain Falling, The Bone Readers, but also Pynter Bender

• Tobias S. Buckell is a science fiction novelist born in Grenada

Curacao (Netherlands)

• Radna Fabias, Habitus is poetry in Dutch, and 9 Dutch poems with English translations online here:

https://www.versopolis-poetry.com/poet/219/radna-fabias

Caribbean Netherlands (Netherlands)

Sint Maarten (Netherlands)

• Lasana M. Sekou is a prolific author, e.g. Brotherhood of the Spurs, and edited Where I See The Sun: Contemporary Poetry in St. Martin

Saint Kitts and Nevis

• Caryl Phillips, novels A State of Independence, The Final Passage, and Cambridge

• Bertram Roach's novel Only God Can Make a Tree

Dominica

• Jean Rhys is famous for the novel Wide Sargasso Sea, but she also wrote a few short stories reflecting her childhood background which are in Sleep It Off Lady

• Phyllis Shand Allfrey, novel The Orchid House, short stories in It Falls into Place, and poetry

• Marie-Elena John, novel Unburnable

Antigua and Barbuda

• Jamaica Kincaid, novels including Annie John, The Autobiography of My Mother, Mr Potter and Lucy, short stories in At the Bottom of the River, and travel essays including A Small Place about Antigua and Talk Stories about the US

Aruba (Netherlands)

• Three of Nydia Ecury's short stories are in The Whistling Bird: Women Writers of the Caribbean edited by Pierrette Frickey

• Henry Habibe is a poet who occasionally writes in Spanish or Dutch

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

• Cecil Browne's short stories in The Moon Is Following Me and Feather Your Tingaling (or Cassie P Caribbean PI if you must)

• H. Nigel Thomas, novels (some set in Canada), Spirits in the Dark has a gay protagonist

• Shake Keane was a legendary jazz trumpeter (and poet)

Grenada

• Merle Collins, Lady in a Boat poetry, Angel and The Colour of Forgetting novels, and The Ladies are Upstairs short stories

• Jean Buffong, novels such as Under the Silk Cotton Tree

• Jacob Ross, mostly crime novels Black Rain Falling, The Bone Readers, but also Pynter Bender

• Tobias S. Buckell is a science fiction novelist born in Grenada

Curacao (Netherlands)

• Radna Fabias, Habitus is poetry in Dutch, and 9 Dutch poems with English translations online here:

https://www.versopolis-poetry.com/poet/219/radna-fabias

4spiralsheep

Caribbean 2

Saint Lucia

• Derek Walcott, Nobel prize winning poetry, famously Omeros

• Garth St. Omer, novels (just read Walcott, mkay?)

• Earl G. Long, novels (or Waallccccootttt!)

Barbados

• Edward Kamau Brathwaite, poetry (bookshop / library search tip: Edward Brathwaite)

• George Lamming, novels including In the Castle of My Skin, essays The Pleasures of Exile

• Austin Clarke, novels including The Polished Hoe, short stories, memoirs and poetry (note: the other poet Aibhistín Ó Cléirigh / Austin Clarke was Irish)

• Timothy Callender, short stories in It So Happen

• Glenville Lovell, novels Fire in the Canes and Song of Night (also writes crime novels set in US)

• Cecil Foster, novels including No Man in the House

• Adisa Andwele, poetry in Bajan nation language Antiquity

• (Note: Inkle & Yarico is a Caribbean classic set in Barbados but Beryl Gilroy was Guyanan-British - she also founded Peepal Tree Press)

• (Note: Paule Marshall was a great novelist but African-American)

Martinique (France)

• Patrick Chamoiseau, novels in French and English including Texaco, Slave Old Man, School Days, and Solibo Magnificent

• Joseph Zobel, novels in French and English including Black Shack Alley

• Aime Cesaire, non-fiction Discourse on Colonialism, and Collected Poetry which presumably includes Notebook of a Return to the Native Land

• Frantz Fanon, non-fiction The Wretched of the Earth

Bahamas

• Ian G. Strachan, novel God's Angry Babies

Gualdeloupe (France)

• Maryse Conde, novels in French with at least 14 English translations including I, Tituba, Black Witch of Salem (set in US), Segu and sequel (set in Mali), Crossing the Mangrove, Windward Heights, and Victoire: My Mother's Mother

• Simone Schwarz-Bart, novels in French and English including The Bridge of Beyond and Between Two Worlds

• Myriam Warner-Vieyra two novels in French and English, As the Sorcerer Said and Juletane (set in Senegal), and short stories in French

• Daniel Maximin novels in French

• Guy Tirolien, poetry in French

Saint Lucia

• Derek Walcott, Nobel prize winning poetry, famously Omeros

• Garth St. Omer, novels (just read Walcott, mkay?)

• Earl G. Long, novels (or Waallccccootttt!)

Barbados

• Edward Kamau Brathwaite, poetry (bookshop / library search tip: Edward Brathwaite)

• George Lamming, novels including In the Castle of My Skin, essays The Pleasures of Exile

• Austin Clarke, novels including The Polished Hoe, short stories, memoirs and poetry (note: the other poet Aibhistín Ó Cléirigh / Austin Clarke was Irish)

• Timothy Callender, short stories in It So Happen

• Glenville Lovell, novels Fire in the Canes and Song of Night (also writes crime novels set in US)

• Cecil Foster, novels including No Man in the House

• Adisa Andwele, poetry in Bajan nation language Antiquity

• (Note: Inkle & Yarico is a Caribbean classic set in Barbados but Beryl Gilroy was Guyanan-British - she also founded Peepal Tree Press)

• (Note: Paule Marshall was a great novelist but African-American)

Martinique (France)

• Patrick Chamoiseau, novels in French and English including Texaco, Slave Old Man, School Days, and Solibo Magnificent

• Joseph Zobel, novels in French and English including Black Shack Alley

• Aime Cesaire, non-fiction Discourse on Colonialism, and Collected Poetry which presumably includes Notebook of a Return to the Native Land

• Frantz Fanon, non-fiction The Wretched of the Earth

Bahamas

• Ian G. Strachan, novel God's Angry Babies

Gualdeloupe (France)

• Maryse Conde, novels in French with at least 14 English translations including I, Tituba, Black Witch of Salem (set in US), Segu and sequel (set in Mali), Crossing the Mangrove, Windward Heights, and Victoire: My Mother's Mother

• Simone Schwarz-Bart, novels in French and English including The Bridge of Beyond and Between Two Worlds

• Myriam Warner-Vieyra two novels in French and English, As the Sorcerer Said and Juletane (set in Senegal), and short stories in French

• Daniel Maximin novels in French

• Guy Tirolien, poetry in French

5spiralsheep

Africa

Seychelles (East African island)

• Arguably eligible, Glynn Burridge's Voices, short stories, is available on kindle

Sao Tome and Principe (West African island)

• Four Poems by Conceicao Lima in Portuguese and English are online here:

https://www.poetrytranslation.org/poems/from/saeo-tome-and-principe

• Olinda Beja, novels in Portuguese

Mayotte (East African island, France)

• Short story by Nassuf Djailani, set in Mayotte and the Comoros, online here:

https://www.wordswithoutborders.org/article/the-crossing-toward-hope

Seychelles (East African island)

• Arguably eligible, Glynn Burridge's Voices, short stories, is available on kindle

Sao Tome and Principe (West African island)

• Four Poems by Conceicao Lima in Portuguese and English are online here:

https://www.poetrytranslation.org/poems/from/saeo-tome-and-principe

• Olinda Beja, novels in Portuguese

Mayotte (East African island, France)

• Short story by Nassuf Djailani, set in Mayotte and the Comoros, online here:

https://www.wordswithoutborders.org/article/the-crossing-toward-hope

6spiralsheep

Europe

Vatican City

• Popes, Catholicism, art, and architecture, or insider conspiracy literature such as...

• Shroud of Secrecy: story of corruption within the Vatican by Millenari

Gibraltar (arguably United Kingdom)

San Marino

• Short story by Roberto Montis online here:

https://theculturetrip.com/europe/articles/read-sammarinese-writer-roberto-monti...

Liechtenstein

• Not eligible for Reading Globally but Paul Gallico, who was American, wrote Ludmila, an illustrated children's folktale

Monaco

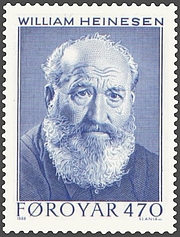

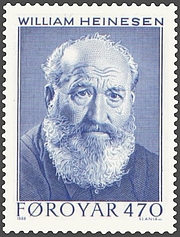

Faroe Islands (arguably Denmark)

• The Old Man and His Sons by Heðin Bru

• The Lost Musicians by William Heinesen

• The Brahmadells by Joanes Nielsen

Greenland (arguably Denmark)

• Last Night in Nuuk (US) aka Crimson (UK) by Niviaq Korneliussen

• The Will of the Unseen is a novel by Hans Lynge

• The Veins of the Heart to the Pinnacle of the Mind is poetry by Aqqaluk Lynge who also has poems online

• A Journey to the Mother of the Sea is an illustrated children's book by Maliaraq Vebaek

• An African in Greenland by Tete-Michel Kpomassie from Togo (note: African-American explorer Matthew Henson, not technically eligible for Reading Globally but certainly a minority author with strong personal connections to Greenland, also wrote A Negro Explorer at the North Pole, 1912, which is available online)

Andorra

Isle of Man (arguably UK)

Channel Islands (Balliwick of Guernsey, Balliwick of Jersey, arguably UK)

Iceland

• You could begin with the creation of Iceland in The Prose Edda

Malta

• Guze Stagno if you read Maltese (someone should translate him!)

• Francis Ebejer, seven novels in English and one in Maltese

• Immanuel Mifsud, novel In the Name of the Father, and poetry The Play of Waves

Vatican City

• Popes, Catholicism, art, and architecture, or insider conspiracy literature such as...

• Shroud of Secrecy: story of corruption within the Vatican by Millenari

Gibraltar (arguably United Kingdom)

San Marino

• Short story by Roberto Montis online here:

https://theculturetrip.com/europe/articles/read-sammarinese-writer-roberto-monti...

Liechtenstein

• Not eligible for Reading Globally but Paul Gallico, who was American, wrote Ludmila, an illustrated children's folktale

Monaco

Faroe Islands (arguably Denmark)

• The Old Man and His Sons by Heðin Bru

• The Lost Musicians by William Heinesen

• The Brahmadells by Joanes Nielsen

Greenland (arguably Denmark)

• Last Night in Nuuk (US) aka Crimson (UK) by Niviaq Korneliussen

• The Will of the Unseen is a novel by Hans Lynge

• The Veins of the Heart to the Pinnacle of the Mind is poetry by Aqqaluk Lynge who also has poems online

• A Journey to the Mother of the Sea is an illustrated children's book by Maliaraq Vebaek

• An African in Greenland by Tete-Michel Kpomassie from Togo (note: African-American explorer Matthew Henson, not technically eligible for Reading Globally but certainly a minority author with strong personal connections to Greenland, also wrote A Negro Explorer at the North Pole, 1912, which is available online)

Andorra

Isle of Man (arguably UK)

Channel Islands (Balliwick of Guernsey, Balliwick of Jersey, arguably UK)

Iceland

• You could begin with the creation of Iceland in The Prose Edda

Malta

• Guze Stagno if you read Maltese (someone should translate him!)

• Francis Ebejer, seven novels in English and one in Maltese

• Immanuel Mifsud, novel In the Name of the Father, and poetry The Play of Waves

7spiralsheep

South East Asia

Brunei

• Written in Black by K.H. Lim, possibly?

Brunei

• Written in Black by K.H. Lim, possibly?

8spiralsheep

Oceania

Tokelau (New Zealand)

• Did you know the language of Tokelau is mutually intelligible with the language of Tuvalu?

Niue (New Zealand)

• John Pule is a diasporan artist, novelist, and poet, living in New Zealand, who has written novels such as The Shark that Ate the Sun, and published art books such as Hiapo and Hauaga

Nauru (Micronesia) and Manus Island (Papua New Guinea)

• Controversially used to imprison refugees seeking asylum in Australia. The most famous books written by inmates are from Manus.

• No Friend but the Mountains: Writing from Manus Prison by Kurdistani refugee Behrouz Boochani

• From Hell to Hell by Ravi (aka S. Nagaveeran) was written on Nauru

Wallis and Fortuna (Polynesia, France)

• Futuna: Mo ona puleaga sau or Aux deux royaumes or The two kingdoms, edited by Elise Huffer and Petelo Leleivai. I know nothing about this book but it appears to have been translated into French and possibly also English

Tuvalu (Polynesia)

• Songs of Tuvalu collected by Gerd Koch, includes 2 CDs and an English translation

Cook Islands (New Zealand)

• The children's novel Miss Ulysses of Puka-Puka, 1948, by Johnny Frisbie was the first published work by any Pacific Islander woman. The Frisbies of the South Seas is also available in English

Palau (Micronesia)

• The Palauan Perspectives: a poetry book by Hermana Ramarui was published in 1984 and is showing its age but it does represent Palau well at that time

Marshall Islands (Micronesia)

• Iep Jaltok: Poems from a Marshallese Daughter by Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner

Tonga (Polynesia)

• Konai Helu Thaman, poetry

• Epeli Hauʻofa, fiction, poetry, and essays

Federated States of Micronesia: Yap, Chuuk, Pohnpei, and Kosrae

• Pohnpei: My Urohs, poetry, by Emelihter Kihleng

• Anthology: Indigenous Literatures from Micronesia

Kiribati (technically in all four hemispheres!)

• Waa in Storms, poetry +, by Teweiariki Teaero

Samoa (Polynesia)

• Albert Wendt, known for his own writing and as an anthology editor

• Sia Figiel, novels including Where We Once Belonged, They Who Do Not Grieve, and Freelove: a novel, and poetry

• Scar of the Bamboo Leaf is a novel by Sieni A.M.

French Polynesia (France)

• Celestine Hitiura Vaite wrote a trilogy of chicklit beginning with Frangipani

Vanuatu (Melanesia)

• Grace Molisa's poetry in Black Stone II, and Colonised People, and the original Black Stone

New Caledonia (Melanesia, France)

• Dewe Gorode's novel Wreck (warnings for sexual abuses, plural)

Tokelau (New Zealand)

• Did you know the language of Tokelau is mutually intelligible with the language of Tuvalu?

Niue (New Zealand)

• John Pule is a diasporan artist, novelist, and poet, living in New Zealand, who has written novels such as The Shark that Ate the Sun, and published art books such as Hiapo and Hauaga

Nauru (Micronesia) and Manus Island (Papua New Guinea)

• Controversially used to imprison refugees seeking asylum in Australia. The most famous books written by inmates are from Manus.

• No Friend but the Mountains: Writing from Manus Prison by Kurdistani refugee Behrouz Boochani

• From Hell to Hell by Ravi (aka S. Nagaveeran) was written on Nauru

Wallis and Fortuna (Polynesia, France)

• Futuna: Mo ona puleaga sau or Aux deux royaumes or The two kingdoms, edited by Elise Huffer and Petelo Leleivai. I know nothing about this book but it appears to have been translated into French and possibly also English

Tuvalu (Polynesia)

• Songs of Tuvalu collected by Gerd Koch, includes 2 CDs and an English translation

Cook Islands (New Zealand)

• The children's novel Miss Ulysses of Puka-Puka, 1948, by Johnny Frisbie was the first published work by any Pacific Islander woman. The Frisbies of the South Seas is also available in English

Palau (Micronesia)

• The Palauan Perspectives: a poetry book by Hermana Ramarui was published in 1984 and is showing its age but it does represent Palau well at that time

Marshall Islands (Micronesia)

• Iep Jaltok: Poems from a Marshallese Daughter by Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner

Tonga (Polynesia)

• Konai Helu Thaman, poetry

• Epeli Hauʻofa, fiction, poetry, and essays

Federated States of Micronesia: Yap, Chuuk, Pohnpei, and Kosrae

• Pohnpei: My Urohs, poetry, by Emelihter Kihleng

• Anthology: Indigenous Literatures from Micronesia

Kiribati (technically in all four hemispheres!)

• Waa in Storms, poetry +, by Teweiariki Teaero

Samoa (Polynesia)

• Albert Wendt, known for his own writing and as an anthology editor

• Sia Figiel, novels including Where We Once Belonged, They Who Do Not Grieve, and Freelove: a novel, and poetry

• Scar of the Bamboo Leaf is a novel by Sieni A.M.

French Polynesia (France)

• Celestine Hitiura Vaite wrote a trilogy of chicklit beginning with Frangipani

Vanuatu (Melanesia)

• Grace Molisa's poetry in Black Stone II, and Colonised People, and the original Black Stone

New Caledonia (Melanesia, France)

• Dewe Gorode's novel Wreck (warnings for sexual abuses, plural)

9spiralsheep

Self governing overseas territories of the UK

Cayman Islands

Bermuda

Turks and Caicos Islands

Gibraltar

(British) Virgin Islands

Anguilla

Saint Helena

Monserrat

Falkland Islands

Overseas territories of the US

American Samoa

Northern Mariana Islands

US Virgin Islands

Guam (arguably Cuba)

Cayman Islands

Bermuda

Turks and Caicos Islands

Gibraltar

(British) Virgin Islands

Anguilla

Saint Helena

Monserrat

Falkland Islands

Overseas territories of the US

American Samoa

Northern Mariana Islands

US Virgin Islands

Guam (arguably Cuba)

10spiralsheep

Enjoy! :-)

11karenb

Barbados: also Karen Lord, science fiction novels and stories (usually science fiction plus, e.g., SF plus a murder mystery and labyrinths in Unraveling).

12rocketjk

How about Gaeltacht, the area within Ireland where Irish is still predominantly the population's first language? As per Wikipedia, there seem to be between 70,000 and 170,000 who use Irish as their first language.

13spiralsheep

>11 karenb: Excellent!

>12 rocketjk: It's your reading. If you want to include minority languages within larger states, anglophone or otherwise, then that's your decision. :-)

Also, arguably: http://www.librarything.com/groups/readinggloballyii1

ETA also this thread: http://www.librarything.com/topic/260611

>12 rocketjk: It's your reading. If you want to include minority languages within larger states, anglophone or otherwise, then that's your decision. :-)

Also, arguably: http://www.librarything.com/groups/readinggloballyii1

ETA also this thread: http://www.librarything.com/topic/260611

14thorold

There was also a great list of writers compiled by RebeccaNYC for the 2015 Caribbean thread (post 8 onwards) https://www.librarything.com/topic/209482#5384242 — obviously you’ll have to skip Haiti, Cuba, Jamaica, etc.

Two of us read Texaco, I think that was the biggest hit from a small island in that theme, highly recommended. But I was glad to have read The arrivants as well.

Two of us read Texaco, I think that was the biggest hit from a small island in that theme, highly recommended. But I was glad to have read The arrivants as well.

15spiralsheep

>14 thorold: I can't see any fiction authors I've missed on the previous thread's list, although there's one I left out deliberately, lol.

I'm planning on reading Jamaica Kincaid's novel Annie John and travel writing about New York in Talk Stories, and if I have time then also Merle Collins' The Ladies are Upstairs or The Colour of Forgetting.

I'm planning on reading Jamaica Kincaid's novel Annie John and travel writing about New York in Talk Stories, and if I have time then also Merle Collins' The Ladies are Upstairs or The Colour of Forgetting.

16kidzdoc

Thanks for this great introduction, spiralsheep! I own at least a dozen unread books that fit this category, three of which are on my list of books to read in 2021, so I'll plan to get to them at least: In the Castle of My Skin by George Lamming, A State of Independence by Caryl Phillips, and Texaco by Patrick Chamoiseau.

17Settings

Extremely nice list and introduction.

For the Caribbean, Peepal Tree Press is searchable by national identity. Listing some extra authors (lots of poetry). Their collection is also searchable by author's residence, place of birth, or by book setting. Broken touchstones are either because I can't spell or because they aren't working. :\

Dominica: Elma Napier (A Flying Fish Whispered)

Grenada: Malika Booker (Pepper Seed) and Jacob Ross (Tell No-One About this, others)

Saint Lucia: Adrian Augier (Navel String), Kendel Hippolyte (Wordplanting, others), Jane King (Performance Anxiety), John Robert Lee (Pierrot, others), Vladimir Lucien (Sounding Ground)

Barbados: Kevyn Alan Arthur (England and Nowhere, others), Christine Barrow, (Black Dogs and the Colour Yellow), Jane Bryce (Chameleon and Other Stories), June Henfrey (Coming Home and Other Stories), Carl Jackson (Nor the Battle to the Strong), Cherie Jones (The Burning Bush Women & Other Stories), Antony Kellamn (Tracing JaJa, others), Sai Murray (Ad-liberation, others), Esther Phillips (The Stone Gatherer, others), Dorothea Smartt (Ship Shape, others)

Bahamas: Robert Antoni (Cut Guavas, others), Marion Bethel (Bougainvillea Ringplay), Christian Campbell (Running the Dusk), Helen Klonaris (If I Had the Wings), Lelawattee Manoo-Rahming (Curry Flavour)

For the Caribbean, Peepal Tree Press is searchable by national identity. Listing some extra authors (lots of poetry). Their collection is also searchable by author's residence, place of birth, or by book setting. Broken touchstones are either because I can't spell or because they aren't working. :\

Dominica: Elma Napier (A Flying Fish Whispered)

Grenada: Malika Booker (Pepper Seed) and Jacob Ross (Tell No-One About this, others)

Saint Lucia: Adrian Augier (Navel String), Kendel Hippolyte (Wordplanting, others), Jane King (Performance Anxiety), John Robert Lee (Pierrot, others), Vladimir Lucien (Sounding Ground)

Barbados: Kevyn Alan Arthur (England and Nowhere, others), Christine Barrow, (Black Dogs and the Colour Yellow), Jane Bryce (Chameleon and Other Stories), June Henfrey (Coming Home and Other Stories), Carl Jackson (Nor the Battle to the Strong), Cherie Jones (The Burning Bush Women & Other Stories), Antony Kellamn (Tracing JaJa, others), Sai Murray (Ad-liberation, others), Esther Phillips (The Stone Gatherer, others), Dorothea Smartt (Ship Shape, others)

Bahamas: Robert Antoni (Cut Guavas, others), Marion Bethel (Bougainvillea Ringplay), Christian Campbell (Running the Dusk), Helen Klonaris (If I Had the Wings), Lelawattee Manoo-Rahming (Curry Flavour)

18Settings

I wanted to read from the books on my world literature book list that I can get.

Nuanua: Pacific Writing in English since 1980 (Kiribati), something by Albert Wendt (Samoa), Nart Sagas (Abkhazia), "Young People of the Pacific Islands" (French Polynesia)

.... and Omeros by Derek Walcott (Saint Lucia). Finally got around to reading The Odyssey specifically to read that one.

Nuanua: Pacific Writing in English since 1980 (Kiribati), something by Albert Wendt (Samoa), Nart Sagas (Abkhazia), "Young People of the Pacific Islands" (French Polynesia)

.... and Omeros by Derek Walcott (Saint Lucia). Finally got around to reading The Odyssey specifically to read that one.

19lilisin

I’m happy I’ll be able to participate for the first time in a long time as I have Texaco on my TBR and as it’s a book my mom has been telling me to read for the past 20 years or so, it’ll be nice to finally get to tell her I read it.

20karenb

(>1 spiralsheep: Oh, I forgot to say thanks for doing all the setup work!)

21spiralsheep

>17 Settings: Thank you for the lovely long list of additions!

Elma Napier was Scottish although she did live in the Caribbean for a long time and I think long-term residents should count if readers want.

Malika Booker was born in London and considers herself British (I've met her!). Her work does deal with the Afro-Caribbean-British experience though, which often includes long visits and temporary residence in various "home" places.

I'm not familiar with all the authors you've listed but anyone reading to fulfil a challenge might need to check their personal criteria for some of those other authors too.

Elma Napier was Scottish although she did live in the Caribbean for a long time and I think long-term residents should count if readers want.

Malika Booker was born in London and considers herself British (I've met her!). Her work does deal with the Afro-Caribbean-British experience though, which often includes long visits and temporary residence in various "home" places.

I'm not familiar with all the authors you've listed but anyone reading to fulfil a challenge might need to check their personal criteria for some of those other authors too.

22Settings

Yeah, Peepal Press could be listing past and current national identities or they are not very accurate / up to date / have their own perspective.

Challenge reading with this kind of thing is a challenge in itself.

Challenge reading with this kind of thing is a challenge in itself.

23spiralsheep

>22 Settings: Peepal Tree Press are an excellent publisher so I'll excuse them if they're not also perfect admins (as long as everyone gets paid what they're owed). :D

24Settings

Posted in the wrong thread. :|

Edit: Gah now I've gotta find something to write that's potentially worth the post.

The Roar of Morning by Tip Marugg is what I have for Curacao on my list (author is possibly not strictly from Curacao but close enough for my purposes). Also read Haiku in Papiamentu, which I did not like, and Carel de Haseth's "Slave and Master", which I didn't like either but admit has a great deal of historical value.

Have also read stuff by Jamaica Kincaid, Jean Rhys, Edward Kamau Brathwaite, and Aime Cesaire, all of which are phenomenal authors.

Edit: Gah now I've gotta find something to write that's potentially worth the post.

The Roar of Morning by Tip Marugg is what I have for Curacao on my list (author is possibly not strictly from Curacao but close enough for my purposes). Also read Haiku in Papiamentu, which I did not like, and Carel de Haseth's "Slave and Master", which I didn't like either but admit has a great deal of historical value.

Have also read stuff by Jamaica Kincaid, Jean Rhys, Edward Kamau Brathwaite, and Aime Cesaire, all of which are phenomenal authors.

25Tess_W

2021 is going to be a "reading from my own shelves" type of year. I want to cut my TBR by 50%. Therefore my choices are limited: The Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys and Burial Rites, a true story in novel form about the last woman executed in Iceland.

26cindydavid4

>24 Settings: Have also read stuff by Jamaica Kincaid, Jean Rhys,

These are the only two I am familiar with and really like their books. Will have to check the other two authors you mentioned

These are the only two I am familiar with and really like their books. Will have to check the other two authors you mentioned

27spiralsheep

Anyone seeking a read-a-like for Wide Sargasso Sea might want to consider Windward Heights by Maryse Condé which is probably also available via many libraries.

28cindydavid4

That looks interesting, but what if you really hated weathering (spelled on purpose) heights and wanted to slap both characters silly? Or will I be pleasantly surprised?

29thorold

>24 Settings: I enjoyed The roar of morning, in a low-key kind of way. Plenty of Curaçao geography there, too.

30spiralsheep

>28 cindydavid4: Lol, I'm probably the wrong person to ask, as I also rolled my eyes at the protags of Wuthering Heights, even when we read it at school (or maybe that was the point - literature as inoculation?). I do find that, as with Wide Sargasso Sea, I often like new perspectives better than the original. I also like sharing info about available options but I rarely rec books to individuals because I think people can decide better for themselves.

You'll know what you want when you see the shiny thing! :-)

You'll know what you want when you see the shiny thing! :-)

31AnnieMod

Icelandic fiction it is for me in Q1 then -- Independent People had been on my TBR for way too long and I have a few Icelandic crime series I need to catch up on. :) And I have The complete sagas of Icelanders, including 49 tales on my shelves.

Not sure if I have anything else suitable but who knows - need to do some digging.

Not sure if I have anything else suitable but who knows - need to do some digging.

32rocketjk

>13 spiralsheep: "It's your reading. If you want to include minority languages within larger states, anglophone or otherwise, then that's your decision. :-)

OK. The topic title doesn't say anything about "states," though. I guess that was what confused me. The Irish speaking western part of the Irish Republic is certainly a linguistically distinct "{place} with under 500,000 inhabitants."

Anyway, my question was basically academic, as I don't have any specific plans to read anything from that part of Ireland in the coming calendar quarter. Carry on!

OK. The topic title doesn't say anything about "states," though. I guess that was what confused me. The Irish speaking western part of the Irish Republic is certainly a linguistically distinct "{place} with under 500,000 inhabitants."

Anyway, my question was basically academic, as I don't have any specific plans to read anything from that part of Ireland in the coming calendar quarter. Carry on!

33spiralsheep

>32 rocketjk: In the planning thread I originally suggest this topic for countries with small populations. The intro and recs list both reflect that. I've included recs for overseas territories which are culturally distinct and fall within the general aims of Reading Globally by being either primarily non-anglophone or anglophone but with restricted access to the major global anglophone publishing industry, mostly because many of them are politically disputed and locals see themselves as a separate "nation" from the colonial power, in hopes of encouraging members to read more widely.

However, people make their own decisions about what to read for any particular topic, and I have no intention of hosting differently to that established group norm.

If someone approaches me for recs for works translated from Irish Gaelic then I can certainly help them.

However, people make their own decisions about what to read for any particular topic, and I have no intention of hosting differently to that established group norm.

If someone approaches me for recs for works translated from Irish Gaelic then I can certainly help them.

34cindydavid4

>30 spiralsheep: I do find that, as with Wide Sargasso Sea, I often like new perspectives better than the original. I also like sharing info about available options but I rarely rec books to individuals

I do as well, which is probably why I love twisted fairy tales (Im leading a Shakespeares Children theme in Reading through Time if anyone is interested in the above) I liked WSS, so I wll see about this one, and won't come down on you to hard for suggesting it to me :)

I do as well, which is probably why I love twisted fairy tales (Im leading a Shakespeares Children theme in Reading through Time if anyone is interested in the above) I liked WSS, so I wll see about this one, and won't come down on you to hard for suggesting it to me :)

35cindydavid4

>31 AnnieMod: My freshman year, I ended up in enrolling in a Scandinavian Lit class coz everything else was full. Ended up being one of my fav classes loved all the sagas, as well as the history and cultural lessons. Sounds like those would be a fun reread for me

36spiphany

If anyone is looking for titles from Liechtenstein, there's a recent German-language novel, Für immer die Alpen by Benjamin Quaderer, which has been getting a lot of media attention.

Armin Öhri is another Liechtenstein author (whose works include the programmatically titled "Liechtenstein: Roman einer Nation", and a number of historical mysteries set mostly in Berlin...) The only thing translated into English that I could find is a volume of poetry by Michael Donhauser.

Armin Öhri is another Liechtenstein author (whose works include the programmatically titled "Liechtenstein: Roman einer Nation", and a number of historical mysteries set mostly in Berlin...) The only thing translated into English that I could find is a volume of poetry by Michael Donhauser.

37alvaret

I'm a bit early but as of last year reading The good shepherd, a novella by Gunnar Gunnarsson (from Iceland), is part of my Christmas tradition. In it we follow the shepherd Benedikt and his dog and tame sheep as they go up in the Icelandic highlands to rescue any left behind sheep before winter properly sets in. As may be guessed from the title it is a deeply Christian novella but not in a preaching or shallow way. Instead it follows a good man's fight against the elements and his relationship with animals, nature, and God. It is poetic and beautiful, so, unless you are allergic to any spiritual readings, I recommend it.

38spiralsheep

I wasn't planning to read this but here I am three days early... I blame temptress cindydavid4.

I read the 1969 play A Tempest by Aime Cesaire that retells Shakespeare's Tempest, set on an island where the European colonial Prospero enforces slavery on a mulatto Ariel and a Black/indigenous Caliban. The text pushes beyond critiquing colonialism and into decolonisation. I read Richard Miller's 1985/1992 anglophone translation but wished I'd also had the original French for side by side comparison.

There are some interesting linguistic choices that aren't from Shakespeare, such as Prospero being "marooned" on the island, and the first scene very pointedly has people participating as players literally choosing their own characters: "You want Caliban? Well, that's revealing." "And there's no problem about the villains either: you, Antonio; you Alonso, perfect!" Caliban's first word is "Uhuru!" (Freedom!). Caliban rejects the slave name foisted on him by Prospero, and wants to be called "X" (like Malcolm, clearly). There's intertextual Baudelaire: "Des hommes dont le corps est mince et vigoureux,/ Et des femmes dont l'oeil par sa franchise étonne." And the play's intellectual coup de grâce is Prospero's choice of taunt at Caliban for not murdering him: "See, you're nothing but an animal... you don't know how to kill." Unlike Prospero and his fellow Europeans, Antonio and Sebastian, who have shown they know how to murder motivated by personal ambition.

In the end we find that Caliban has always been free in his own mind while Prospero continues to enslave himself to his desire for power over others.

ETA: Some context for Aime Cesaire's play The Tempest, published 1969, from Ryszard Kapuscinski's book Travels with Herodotus; a description of the Premier Festival Mondial des Arts Negres, Dakar, Senegal, 1963: "Theatrical performances abound in the streets and the squares. African theatre is not as formalistic as the European. A group of people can gather someplace extemporaneously and perform an impromptu play. There is no text; everything is the product of the moment, of the passing mood, of spontaneous imagination. The subject can be anything:" (my note: anything that is a shared story which can be improvised around, from daily life to texts such as Shakespeare's The Tempest to traditional oral myths and legends.) The subject matter must be simple, the language comprehensible to all." /para/ "Someone has an idea and volunteers to be director. He assigns roles and the play begins."

I read the 1969 play A Tempest by Aime Cesaire that retells Shakespeare's Tempest, set on an island where the European colonial Prospero enforces slavery on a mulatto Ariel and a Black/indigenous Caliban. The text pushes beyond critiquing colonialism and into decolonisation. I read Richard Miller's 1985/1992 anglophone translation but wished I'd also had the original French for side by side comparison.

There are some interesting linguistic choices that aren't from Shakespeare, such as Prospero being "marooned" on the island, and the first scene very pointedly has people participating as players literally choosing their own characters: "You want Caliban? Well, that's revealing." "And there's no problem about the villains either: you, Antonio; you Alonso, perfect!" Caliban's first word is "Uhuru!" (Freedom!). Caliban rejects the slave name foisted on him by Prospero, and wants to be called "X" (like Malcolm, clearly). There's intertextual Baudelaire: "Des hommes dont le corps est mince et vigoureux,/ Et des femmes dont l'oeil par sa franchise étonne." And the play's intellectual coup de grâce is Prospero's choice of taunt at Caliban for not murdering him: "See, you're nothing but an animal... you don't know how to kill." Unlike Prospero and his fellow Europeans, Antonio and Sebastian, who have shown they know how to murder motivated by personal ambition.

In the end we find that Caliban has always been free in his own mind while Prospero continues to enslave himself to his desire for power over others.

ETA: Some context for Aime Cesaire's play The Tempest, published 1969, from Ryszard Kapuscinski's book Travels with Herodotus; a description of the Premier Festival Mondial des Arts Negres, Dakar, Senegal, 1963: "Theatrical performances abound in the streets and the squares. African theatre is not as formalistic as the European. A group of people can gather someplace extemporaneously and perform an impromptu play. There is no text; everything is the product of the moment, of the passing mood, of spontaneous imagination. The subject can be anything:" (my note: anything that is a shared story which can be improvised around, from daily life to texts such as Shakespeare's The Tempest to traditional oral myths and legends.) The subject matter must be simple, the language comprehensible to all." /para/ "Someone has an idea and volunteers to be director. He assigns roles and the play begins."

39Settings

>38 spiralsheep:

Nice choice! We read that for Western Humanities class. I remember it fondly but not clearly.

A topic on classic literature reworks could have an entire Caribbean section. A Tempest, Omeros, Wide Sargasso Sea, Windward Heights (I feel like there are many more...). I want to comment further on this but too difficult to phrase without falling into generalities, so going to not, haha.

Nice choice! We read that for Western Humanities class. I remember it fondly but not clearly.

A topic on classic literature reworks could have an entire Caribbean section. A Tempest, Omeros, Wide Sargasso Sea, Windward Heights (I feel like there are many more...). I want to comment further on this but too difficult to phrase without falling into generalities, so going to not, haha.

40spiralsheep

>39 Settings: Yes, or expand it into a worldwide theme to include works such as A Grain of Wheat by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o (Tempest, Kenya) and We that are Young by Preti Taneja (King Lear, India) etc.

41thorold

>39 Settings: ...and a sub-section on writers from big countries stealing the idea, as in Coetzee’s Foe and Marina Warner’s Indigo

42cindydavid4

>38 spiralsheep: bwahahaha! My work here is done! Read that post in the shakepears children thread that looks really good. Saw it on Amazon and its now in my cart Looking forward to reading it!

43spiralsheep

>42 cindydavid4: :D

I read the Richard Miller translation, because I was offered a copy, but I think there's at least one other English translation. Reading the play was a 3.5/5 for me but I suspect it would be much more fun to produce. The script was loose enough to allow different interpretations, from broadly comedic to pointedly political.

I read the Richard Miller translation, because I was offered a copy, but I think there's at least one other English translation. Reading the play was a 3.5/5 for me but I suspect it would be much more fun to produce. The script was loose enough to allow different interpretations, from broadly comedic to pointedly political.

44spiralsheep

Happy Gregorian rollover!

I decided to try noticing if these places have anything in common, in addition to mostly being islands or small coastal lands. I'm scouting for mentions of the sea, the shore, fishing and fishermen, seafood, etc. So it was amusing to read in my first book for this theme:

"I now live in Manhattan. The only thing it has in common with the island where I grew up is a geographical definition."

Talk Stories by Jamaica Kincaid (Antiguan-American) is a compilation of autobiographical essays taken from the New Yorker magazine's Talk of the Town section from 1974-83. Some are local gossip column style, some are sociology disguised as gossip, and some are travel writing disguised as sociological gossip. The first essay, which Jamaica Kincaid didn't expect to be printed without more editing, ends with an excellent carnival clowning joke referencing Malcolm X. The subsequent essays are more sedate, as one would expect from a marginalised writer trying to fit into the mainstream, but all of them are professionally written and retain more interest than might be imagined for pieces printed as 1970s gossip columns.

Quotes

Carnival clowning, 1974: "As Lord Kitchener said to me, 'accessibility is the key to success.' After that I had a large hunk of Shabazz Bean Pie. I say without reservation, this is the No.1 Third World dessert. In fact, every time I have some of it I think kindly of Mr Shabazz and everybody with an 'X' after his name."

Advice from editors, 1979, lol: "A fiction writer can write about anorexia nervosa, abortion, death, and homosexuality in hard-cover books for young adults but not in soft-cover books for young adults."

Lmao, 1981: "The other day, the people at the Ford Motor Company threw a cocktail party for Anne and Charlotte Ford at the new Palace Hotel. Almost all the guests there looked as though they never drove themselves anywhere or, if they did, they didn't actually have to."

I decided to try noticing if these places have anything in common, in addition to mostly being islands or small coastal lands. I'm scouting for mentions of the sea, the shore, fishing and fishermen, seafood, etc. So it was amusing to read in my first book for this theme:

"I now live in Manhattan. The only thing it has in common with the island where I grew up is a geographical definition."

Talk Stories by Jamaica Kincaid (Antiguan-American) is a compilation of autobiographical essays taken from the New Yorker magazine's Talk of the Town section from 1974-83. Some are local gossip column style, some are sociology disguised as gossip, and some are travel writing disguised as sociological gossip. The first essay, which Jamaica Kincaid didn't expect to be printed without more editing, ends with an excellent carnival clowning joke referencing Malcolm X. The subsequent essays are more sedate, as one would expect from a marginalised writer trying to fit into the mainstream, but all of them are professionally written and retain more interest than might be imagined for pieces printed as 1970s gossip columns.

Quotes

Carnival clowning, 1974: "As Lord Kitchener said to me, 'accessibility is the key to success.' After that I had a large hunk of Shabazz Bean Pie. I say without reservation, this is the No.1 Third World dessert. In fact, every time I have some of it I think kindly of Mr Shabazz and everybody with an 'X' after his name."

Advice from editors, 1979, lol: "A fiction writer can write about anorexia nervosa, abortion, death, and homosexuality in hard-cover books for young adults but not in soft-cover books for young adults."

Lmao, 1981: "The other day, the people at the Ford Motor Company threw a cocktail party for Anne and Charlotte Ford at the new Palace Hotel. Almost all the guests there looked as though they never drove themselves anywhere or, if they did, they didn't actually have to."

45thorold

>44 spiralsheep: I'm scouting for mentions of the sea, the shore, fishing and fishermen, seafood, etc.

I decided to start with Liechtenstein, following up one of the hints in >36 spiphany: — no sea-shore, of course, but, being in a flat-bottomed stretch of the Rhine valley between the mountains and Lake Constance, they have had their fair share of floods, apparently. I'm just reading about the one in 1927. (picture here: https://historisches-lexikon.li/index.php?title=Datei:Ueberschwemmungen.jpg&...; )

I decided to start with Liechtenstein, following up one of the hints in >36 spiphany: — no sea-shore, of course, but, being in a flat-bottomed stretch of the Rhine valley between the mountains and Lake Constance, they have had their fair share of floods, apparently. I'm just reading about the one in 1927. (picture here: https://historisches-lexikon.li/index.php?title=Datei:Ueberschwemmungen.jpg&...; )

46spiralsheep

>45 thorold: Wow. We have flash flooding here despite the steepness - 2ft deep outside my friends' door last week - but, as you observe, it all runs down into the wide river valley below.

I was thinking that another aspect these places have in common is perhaps linguistic multinationalism, through sharing languages with larger neighbours or creoles / patois / pidgens / colonial languages. So Liechtenstein and Antigua would share that similarity. I'm sure there are other similarities too if people choose to pay attention.

I was thinking that another aspect these places have in common is perhaps linguistic multinationalism, through sharing languages with larger neighbours or creoles / patois / pidgens / colonial languages. So Liechtenstein and Antigua would share that similarity. I'm sure there are other similarities too if people choose to pay attention.

47thorold

>44 spiralsheep: As Lord Kitchener said to me, 'accessibility is the key to success.' — it took me a moment to put that one in context and work out which Lord Kitchener Kincaid was talking about there. The Windrush one, not the Khartoum one, evidently...!

48cindydavid4

>44 spiralsheep: Ive enjoyed kincaid's novels Lucy and A Small Place and think I've read some of her essays; would like to read that collection

49spiralsheep

>47 thorold: Yes, that was clearer in the carnival context, but I suspect the comparative inaccessibility of a Shabazz / X joke to the New Yorker audience was intentional following on from "As Lord Kitchener said to me, 'accessibility is the key to success.' " Kincaid did say she didn't expect her notes to be published without edits.

50spiralsheep

>48 cindydavid4: Talk Stories is a light and amusing collection and I enjoyed it but I wouldn't want to read all 77 pieces in one sitting. The essays are well written, as you'd expect from Kincaid, although not as well as Annie John, which I'm currently reading, and some of them have experimental forms although not extreme experiments as they were published in the New Yorker. I wouldn't prioritise it above much of her other work but it's a fun palate cleanser.

51spiralsheep

I case anyone is still confused, Lord Kitchener's calypso song London is the Place for Me (now possibly better known as That One From Paddington), 3mins:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dGt21q1AjuI

:D

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dGt21q1AjuI

:D

52LolaWalser

Hah! What a small (online) world it is:

https://www.librarything.com/topic/317445#7277382

Not sure what to do with this theme. I'm not feeling the connection between literature and population size at all. Seems random, like "read books with a blue cover". I think I'll just wait and see what y'all do with it.

https://www.librarything.com/topic/317445#7277382

Not sure what to do with this theme. I'm not feeling the connection between literature and population size at all. Seems random, like "read books with a blue cover". I think I'll just wait and see what y'all do with it.

53spiralsheep

>52 LolaWalser: You'd probably like Calypso Rose's song/video Young Boy in which she mocks men who chase after partners who're too young for them.

"I'm not feeling the connection between literature and population size at all."

Apart from the sense of struggling to find one's own language and audience, I've noticed a sense of social claustrophobia, e.g. in Jamaica Kincaid's work. If you live on an island with fewer than 65,000 people, which is smaller than my nearest market town, then your extended social network includes most of the inhabitants one way or another: one main street and market where most people shop, few schools, and limited public social opportunities. The respectable people all attend the same churches and the disreputable people all drink in the same bars. Even with traffic between islands, and people coming and going for higher education and work, everyone knows you because you all see each other all the time. Little real privacy and no secrets. And people who live at the margins, either socially or geographically, are highly visible when they do make appearances.

"I'm not feeling the connection between literature and population size at all."

Apart from the sense of struggling to find one's own language and audience, I've noticed a sense of social claustrophobia, e.g. in Jamaica Kincaid's work. If you live on an island with fewer than 65,000 people, which is smaller than my nearest market town, then your extended social network includes most of the inhabitants one way or another: one main street and market where most people shop, few schools, and limited public social opportunities. The respectable people all attend the same churches and the disreputable people all drink in the same bars. Even with traffic between islands, and people coming and going for higher education and work, everyone knows you because you all see each other all the time. Little real privacy and no secrets. And people who live at the margins, either socially or geographically, are highly visible when they do make appearances.

54spiralsheep

>53 spiralsheep: To add a different example of the same close social inter-relatedness: my Icelandic friends can all recite lists of their ancestors, exactly like their ancestors in the sagas many generations ago. So that's closeness through historical time rather than physical space, but I'm guessing it has similar effects on people's minds. Most Icelanders are related to each other whether they want to be or not.

55thorold

Yes, I'm picking up a lot of social inter-relatedness here too. Also a sense that when you live in a small country, independence comes at the cost of being nice to your large neighbours, and it also seems to involve acceptance that you aren't going to be able to enjoy the same kind of individual liberties (political and social) that you do in a bigger place.

This is my first read for the theme:

---

Liechtenstein is 160 km² and has a population of around 39 000 (around 10 000 in 1945). For the potted history, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liechtenstein

Nauru is 21 km² and has a population of around 10 000

I visited the country on a business trip about 20 years ago (nothing to do with secret trusts or bags of banknotes, I was there to look at high-tech machinery!) — to all intents and purposes it seemed like a perfectly normal Swiss canton, the only obvious difference was in the number of banks in Vaduz.

Öhri's a Liechtensteiner who grew up in Ruggel and is president of the Liechtenstein writers' club, but now lives just over the border in Canton St Gallen. He's previously written a series of crime novels set in Bismarck's Berlin.

Liechtenstein - Roman einer Nation (2016) by Armin Öhri (Liechtenstein, 1978- )

This is one of those postmodern novels that is all about the adventures of a (fictional) writer with the same name as the author who is researching a book about a particular topic, and where you are kept guessing for a long time about what is going to turn out to be true and what fictional, rather like the things W G Sebald, Javier Cercas or Laurent Binet do. But with the additional twist that in this case the narrator is going through some kind of neurological illness as he's writing the book, so you're even less sure you can trust his experiences...

The narrator has been hired by a prominent Liechtenstein law firm to write a biography of the firm's founder, Wilhelm Anton Risch, conveniently born around 1920 to coincide with the re-launch of the sovereign state of Liechtenstein after the ruling family got kicked off their main estates in Czechoslovakia at the end of the First World War and had to move to the less cosy surroundings of their odd little land-holding in the upper Rhine valley. Risch experiences the disastrous floods of 1927, gets caught up in the fledgling Liechtenstein Nazi youth movement, has to go into exile after the abortive Putsch in March 1939, and serves in the German army during World War II. After the war he travels the world, spending time in the even smaller country of Nauru, then returns to Liechtenstein to practice law and manage trusts.

This gives Öhri plenty of scope to look at some of the less edifying aspects of Liechtenstein history in the 20th century, in particular the high incidence of selective memory loss among former Nazis (and their reluctance to let anyone write about national history), as well as a small selection of the most interesting financial scandals. Through Risch's daughter, he also finds space to tell us about the embarrassingly slow progress of the campaign to give women the vote — successful only after the third referendum, in 1984(!), when the proposition was passed by the narrowest of margins after a rare personal appeal to voters by the ruling prince. And the famous 2003 constitution, widely touted as the least democratic in Europe, which essentially gives the prince powers to do whatever he likes, regardless of voters or parliament.

But there are positive things as well: the pleasanter sides of living in a country where everyone knows everyone else's relatives. Öhri tells us a couple of times that the usual Liechtenstein enquiry to a stranger is "Wem Ghörst?" (Who are your folks?), and that the "Du" form is standard between Liechtensteiners. And the one reasonably positive story in Liechtenstein's history of international relations, when it was the only country in Western Europe to refuse Stalin's requests for forcible repatriation of Soviet citizens after World War II. A central episode in the early part of the book is the flight of the 500 men of General Smyslovsky's First Russian National Army, who had fought on the German side in the war, to seek asylum in Liechtenstein in May 1945. Öhri makes his character Risch a medical officer in Smyslovsky's force. It turns out that Öhri has a personal connection here: as a toddler he unwittingly photo-bombed the unveiling of a monument to the border-crossing of the Russians, and he reproduces the resulting charming snapshot of his younger self side-by-side with the general.

There's a strong Tintin flavour to the early career of Risch, at its most extreme when, aged 17, he is sent to Berlin as envoy of the Volksdeutsche youth movement in Liechtenstein, and he and his little dog are granted an audience with Hitler, but continuing with his journey across Russia and the Pacific (complete with shipwreck). It almost looks as though Öhri didn't notice he was doing this at first, then caught himself at it and decided to turn it into a joke against himself: his Russian chapter is called "Im Lande der Sowjets"!

Probably too many different things going on here to make a really strong novel, and all the characters apart from the country itself turn out to be rather elusive, but Öhri is a fluent and competent writer, and it reads like a good, page-turning crime thriller, postmodern flourishes notwithstanding.

This is my first read for the theme:

---

Liechtenstein is 160 km² and has a population of around 39 000 (around 10 000 in 1945). For the potted history, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liechtenstein

Nauru is 21 km² and has a population of around 10 000

I visited the country on a business trip about 20 years ago (nothing to do with secret trusts or bags of banknotes, I was there to look at high-tech machinery!) — to all intents and purposes it seemed like a perfectly normal Swiss canton, the only obvious difference was in the number of banks in Vaduz.

Öhri's a Liechtensteiner who grew up in Ruggel and is president of the Liechtenstein writers' club, but now lives just over the border in Canton St Gallen. He's previously written a series of crime novels set in Bismarck's Berlin.

Liechtenstein - Roman einer Nation (2016) by Armin Öhri (Liechtenstein, 1978- )

This is one of those postmodern novels that is all about the adventures of a (fictional) writer with the same name as the author who is researching a book about a particular topic, and where you are kept guessing for a long time about what is going to turn out to be true and what fictional, rather like the things W G Sebald, Javier Cercas or Laurent Binet do. But with the additional twist that in this case the narrator is going through some kind of neurological illness as he's writing the book, so you're even less sure you can trust his experiences...

The narrator has been hired by a prominent Liechtenstein law firm to write a biography of the firm's founder, Wilhelm Anton Risch, conveniently born around 1920 to coincide with the re-launch of the sovereign state of Liechtenstein after the ruling family got kicked off their main estates in Czechoslovakia at the end of the First World War and had to move to the less cosy surroundings of their odd little land-holding in the upper Rhine valley. Risch experiences the disastrous floods of 1927, gets caught up in the fledgling Liechtenstein Nazi youth movement, has to go into exile after the abortive Putsch in March 1939, and serves in the German army during World War II. After the war he travels the world, spending time in the even smaller country of Nauru, then returns to Liechtenstein to practice law and manage trusts.

This gives Öhri plenty of scope to look at some of the less edifying aspects of Liechtenstein history in the 20th century, in particular the high incidence of selective memory loss among former Nazis (and their reluctance to let anyone write about national history), as well as a small selection of the most interesting financial scandals. Through Risch's daughter, he also finds space to tell us about the embarrassingly slow progress of the campaign to give women the vote — successful only after the third referendum, in 1984(!), when the proposition was passed by the narrowest of margins after a rare personal appeal to voters by the ruling prince. And the famous 2003 constitution, widely touted as the least democratic in Europe, which essentially gives the prince powers to do whatever he likes, regardless of voters or parliament.

But there are positive things as well: the pleasanter sides of living in a country where everyone knows everyone else's relatives. Öhri tells us a couple of times that the usual Liechtenstein enquiry to a stranger is "Wem Ghörst?" (Who are your folks?), and that the "Du" form is standard between Liechtensteiners. And the one reasonably positive story in Liechtenstein's history of international relations, when it was the only country in Western Europe to refuse Stalin's requests for forcible repatriation of Soviet citizens after World War II. A central episode in the early part of the book is the flight of the 500 men of General Smyslovsky's First Russian National Army, who had fought on the German side in the war, to seek asylum in Liechtenstein in May 1945. Öhri makes his character Risch a medical officer in Smyslovsky's force. It turns out that Öhri has a personal connection here: as a toddler he unwittingly photo-bombed the unveiling of a monument to the border-crossing of the Russians, and he reproduces the resulting charming snapshot of his younger self side-by-side with the general.

There's a strong Tintin flavour to the early career of Risch, at its most extreme when, aged 17, he is sent to Berlin as envoy of the Volksdeutsche youth movement in Liechtenstein, and he and his little dog are granted an audience with Hitler, but continuing with his journey across Russia and the Pacific (complete with shipwreck). It almost looks as though Öhri didn't notice he was doing this at first, then caught himself at it and decided to turn it into a joke against himself: his Russian chapter is called "Im Lande der Sowjets"!

Probably too many different things going on here to make a really strong novel, and all the characters apart from the country itself turn out to be rather elusive, but Öhri is a fluent and competent writer, and it reads like a good, page-turning crime thriller, postmodern flourishes notwithstanding.

56spiralsheep

>55 thorold: Interesting comparison of Liechtenstein and Nauru by population and geographical size (especially with Liechtenstein's population growing while Nauru's geography shrinks under rising sea levels).

"the re-launch of the sovereign state of Liechtenstein after the ruling family got kicked off their main estates in Czechoslovakia at the end of the First World War"

We have some, mostly absentee, second-home owners around here too but not quite on that scale.

"This gives Öhri plenty of scope to look at some of the less edifying aspects of Liechtenstein history in the 20th century, in particular the high incidence of selective memory loss among former Nazis"

If you want to compare former Nazis then Requiem for a Malta Fascist by Francis Ebejer fits this topic.

"the embarrassingly slow progress of the campaign to give women the vote — successful only after the third referendum, in 1984(!)"

Quoted for truth: "to all intents and purposes it seemed like a perfectly normal Swiss canton" (not until 1971 to 1991)

Sounds an interesting read.

"the re-launch of the sovereign state of Liechtenstein after the ruling family got kicked off their main estates in Czechoslovakia at the end of the First World War"

We have some, mostly absentee, second-home owners around here too but not quite on that scale.

"This gives Öhri plenty of scope to look at some of the less edifying aspects of Liechtenstein history in the 20th century, in particular the high incidence of selective memory loss among former Nazis"

If you want to compare former Nazis then Requiem for a Malta Fascist by Francis Ebejer fits this topic.

"the embarrassingly slow progress of the campaign to give women the vote — successful only after the third referendum, in 1984(!)"

Quoted for truth: "to all intents and purposes it seemed like a perfectly normal Swiss canton" (not until 1971 to 1991)

Sounds an interesting read.

57spiralsheep

I read Annie John by Jamaica Kincaid, which is a bildungsroman set in Antigua. It's well written and the descriptions are interesting enough to be a 4* read, but unfortunately I didn't find the protagonist personally engaging.

When describing language, the story doesn't distinguish between the familiarity of Leeward Islands Creole and Standard English but does mark out the unfamiliarity of the protagonist's mother's "French patois" from Dominica.

Both Jamaica Kincaid's non-fiction Talk Stories, which I read recently, and Annie John anticipate and revel in the potential anonymity of big city life compared to individual visibility on a small island.

And in Annie John the surrounding sea is ever present.

But I'll let the following quotes speak for the book.

Quotes

Fish, lying: "When I got home, my mother asked me for the fish I was to have picked up from Mr. Earl, one of our fishermen, on the way home from school. But in my excitement I had completely forgotten. Trying to think quickly, I said that when I got to the market Mr. Earl told me that they hadn’t gone to sea that day because the sea was too rough. “Oh?” said my mother, and uncovered a pan in which were lying, flat on their sides and covered with lemon juice and butter and onions, three fish: an angelfish for my father, a kanya fish for my mother, and a lady doctor fish for me - the special kind of fish each of us liked. While I was at the funeral parlor, Mr. Earl had got tired of waiting for me and had brought the fish to our house himself."

Swimming, or not: "My mother was a superior swimmer. When she plunged into the seawater, it was as if she had always lived there. She would go far out if it was safe to do so, and she could tell just by looking at the way the waves beat if it was safe to do so. She could tell if a shark was nearby, and she had never been stung by a jellyfish. I, on the other hand, could not swim at all. In fact, if I was in water up to my knees I was sure that I was drowning. My mother had tried everything to get me swimming, from using a coaxing method to just throwing me without a word into the water. Nothing worked. The only way I could go into the water was if I was on my mother’s back, my arms clasped tightly around her neck, and she would then swim around not too far from the shore. It was only then that I could forget how big the sea was, how far down the bottom could be, and how filled up it was with things that couldn’t understand a nice hallo. When we swam around in this way, I would think how much we were like the pictures of sea mammals I had seen, my mother and I, naked in the seawater, my mother sometimes singing to me a song in a French patois I did not yet understand, or sometimes not saying anything at all. I would place my ear against her neck, and it was as if I were listening to a giant shell, for all the sounds around me - the sea, the wind, the birds screeching - would seem as if they came from inside her, the way the sounds of the sea are in a seashell. Afterward, my mother would take me back to the shore, and I would lie there just beyond the farthest reach of a big wave and watch my mother as she swam and dove."

Abandoned lighthouse as panopticon: "The Red Girl and I walked to the top of the hill behind my house. At the top of the hill was an old lighthouse. It must have been a useful lighthouse at one time, but now it was just there for mothers to say to their children, “Don’t play at the lighthouse,” my own mother leading the chorus, I am sure. Whenever I did go to the lighthouse behind my mother’s back, I would have to gather up all my courage to go to the top, the height made me so dizzy. But now I marched boldly up behind the Red Girl as if at the top were my own room, with all my familiar comforts waiting for me. At the top, we stood on the balcony and looked out toward the sea. We could see some boats coming and going; we could see some children our own age coming home from games; we could see some sheep being driven home from pasture; we could see my father coming home from work."

When describing language, the story doesn't distinguish between the familiarity of Leeward Islands Creole and Standard English but does mark out the unfamiliarity of the protagonist's mother's "French patois" from Dominica.

Both Jamaica Kincaid's non-fiction Talk Stories, which I read recently, and Annie John anticipate and revel in the potential anonymity of big city life compared to individual visibility on a small island.

And in Annie John the surrounding sea is ever present.

But I'll let the following quotes speak for the book.

Quotes

Fish, lying: "When I got home, my mother asked me for the fish I was to have picked up from Mr. Earl, one of our fishermen, on the way home from school. But in my excitement I had completely forgotten. Trying to think quickly, I said that when I got to the market Mr. Earl told me that they hadn’t gone to sea that day because the sea was too rough. “Oh?” said my mother, and uncovered a pan in which were lying, flat on their sides and covered with lemon juice and butter and onions, three fish: an angelfish for my father, a kanya fish for my mother, and a lady doctor fish for me - the special kind of fish each of us liked. While I was at the funeral parlor, Mr. Earl had got tired of waiting for me and had brought the fish to our house himself."